Pages 399-414 | Received 22 Oct 2013, Accepted 02 May 2014, Published online: 06 Jun 2014

International Journal of Social Research Methodology

Volume 18, 2015 – Issue 4

Abstract

This paper discusses issues of research design and methods in new materialist social inquiry, an approach that is attracting increasing interest across the social sciences as an alternative to either realist or constructionist ontologies. New materialism de-privileges human agency, focusing instead upon how assemblages of the animate and inanimate together produce the world, with fundamental implications for social inquiry methodology and methods. Key to our exploration is the materialist notion of a ‘research-assemblage’ comprising researcher, data, methods and contexts. We use this understanding first to explore the micropolitics of the research process, and then – along with a review of 30 recent empirical studies – to establish a framework for materialist social inquiry methodology and methods. We discuss the epistemological consequences of adopting a materialist ontology.

Introduction

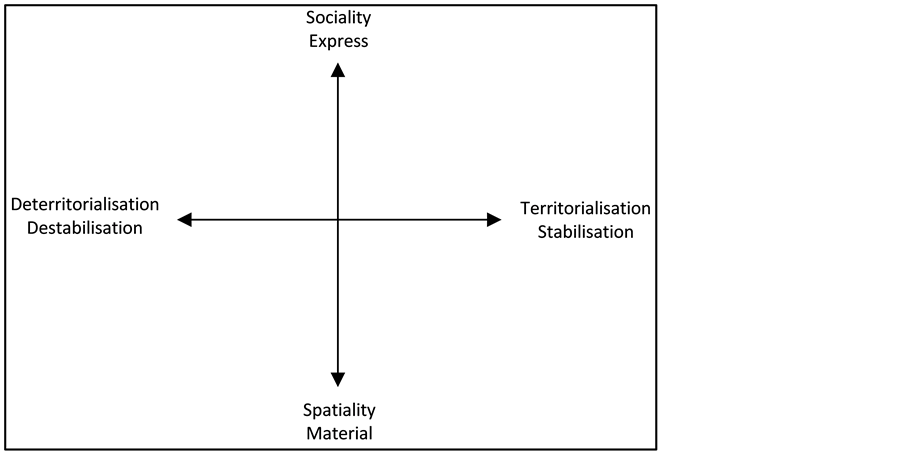

‘New’ (or ‘neo’) materialism has emerged over the past 20 years as an approach concerned fundamentally with the material workings of power, but focused firmly upon social production rather than social construction (Coole & Frost, 2010Coole, D. H., & Frost, S.(2010). New materialisms: Ontology, agency, and politics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.10.1215/9780822392996[Crossref], [Google Scholar], p. 7). Applied to empirical research, it radically extends traditional materialist analysis beyond traditional concerns with structural and ‘macro’ level social phenomena (van der Tuin & Dolphijn, 2010van der Tuin, I., & Dolphijn, R. (2010). The transversality of new materialism. Women: A Cultural Review, 21, 153–171.[Taylor & Francis Online], [Google Scholar], p. 159), addressing issues of how desires, feelings and meanings also contribute to social production (Braidotti, 2000Braidotti, R. (2000). Teratologies. In I.Buchanan & C.Colebrook (Eds.), Deleuze and feminist theory (pp. 156–172). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar], p. 159; DeLanda, 2006DeLanda, M. (2006). A new philosophy of society. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar], p. 5). New materialist ontology breaks through ‘the mind-matter and culture-nature divides of transcendental humanist thought’ (van der Tuin & Dolphijn, 2010van der Tuin, I., & Dolphijn, R. (2010). The transversality of new materialism. Women: A Cultural Review, 21, 153–171.[Taylor & Francis Online], [Google Scholar], p. 155), and is consequently also transversal to a range of social theory dualisms such as structure/agency, reason/emotion, human/non-human, animate/inanimate and inside/outside. It supplies a conception of agency not tied to human action, shifting the focus for social inquiry from an approach predicated upon humans and their bodies, examining instead how relational networks or assemblages of animate and inanimate affect and are affected (DeLanda, 2006DeLanda, M. (2006). A new philosophy of society. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar], p. 4; Mulcahy, 2012Mulcahy, D. (2012). Affective assemblages: Body matters in the pedagogic practices of contemporary school classrooms. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 20, 9–27.[Taylor & Francis Online], [Google Scholar], p. 10; Youdell & Armstrong, 2011Youdell, D., & Armstrong, F. (2011). A politics beyond subjects: The affective choreographies and smooth spaces of schooling. Emotion, Space and Society, 4, 144–150.10.1016/j.emospa.2011.01.002[Crossref], [Google Scholar], p. 145).

These moves pose fundamental questions about how research should be conducted within a new materialist paradigm, and what kinds of data should be collected and analysed. This paper addresses the methodological challenges facing those who wish to apply new materialist ontology to social research. Our point of entry is by considering research as assemblage, a key concept in the materialist ontology that we discuss in the first part of the paper. The research-assemblage (Fox & Alldred, 2013Fox, N. J., & Alldred, P.(2013). The sexuality-assemblage: Desire, affect, anti-humanism. Sociological Review, 61, 769–789.[Crossref], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]; Coleman & Ringrose, 2013Coleman, R., & Ringrose, J. (2013). Introduction. In R.Coleman & J. Ringrose(Eds.), Deleuze and research methodologies(pp. 1–22). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar], p. 17; Masny, 2013Masny, D. (2013). Rhizoanalytic pathways in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 19, 339–348.10.1177/1077800413479559[Crossref], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar], p. 340) comprises the bodies, things and abstractions that get caught up in social inquiry, including the events that are studied, the tools, models and precepts of research, and the researchers. In conjunction with a review of 30 empirical studies using new materialist ontology, this analysis suggests principles for new materialist research designs and methods.