A City In-Between

Riowang

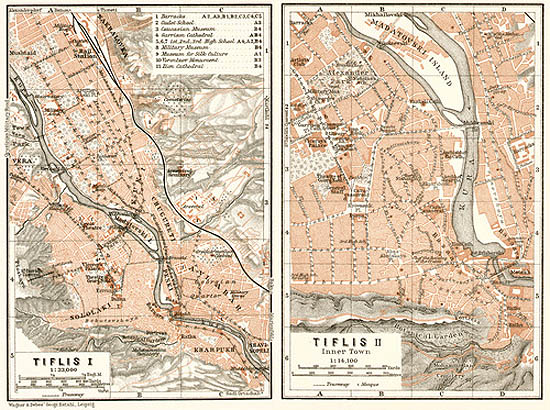

You can still find your way in Tbilisi with the old maps of the city published by the Baedeker on Russia in 1914 or of the guide of Moskvich from 1913. But as to the details, everything has changed, as the city hugely expanded, especially to the west and north. So in this city there is a “Europe” in the west – with absolutely no originality –, while to the south or to the east it seems that you have arrived to the Orient.“Europe” is of course where the city expanded in the twentieth century. The windows have preserved all their glasses, there is hot water on all floors, the apartments perhaps were not divided in 1937, after the disappearance of their occupants, the stairs have no missing steps, no metal or concrete block clutters up the yard, the facade was not riddled with bullets in 1991, you do not have to illuminate the corridors with your mobile phone, you do not share the entrance hall of your apartment with a cantankerous neighbor, nobody hangs the clothes in the yard.

What you find in the east and south, is not necessarily the Orient, but it is neither quite Europe any more, and it is this in-between where the city we love and its people thrive: a world in turn asleep or full of vitality; some spaces crumbling slowly and with indifference, and others being vigorously rebuilt; a city stepping forward from a very distant time with its churches dating to the sixth century, several cities in the city inherited from hostile empires – some of which disappeared by now and some others faded, but still alive – that seem to have born spontaneously from the dynamism of their inhabitants; a world where memory and oblivion meet face to face.

In these obviously dilapidated quarters, at any time you walk the dusty streets, you see children playing and others carrying their schoolbag on the back, cats spinning between your legs, women with their bags going to buy things, men lost in the engine of a car getting ever older. On New Year’s Eve everybody shot their fireworks here, rockets and flares fly out of every window. And in the night, to celebrate the new year, men dressed in black dance together in a circle in front of their cars with open doors, and with the radio turned on to the maximum.

There is also the “Armenian” neighborhood – small houses, or even shacks, clinging to the slope of a ravine plowed by the rains just behind the glass roof of the presidential palace. I take a photo of a house, a man comes out and thanks to me. He knows France, his brother lives in Blois. When he went to see him, he visited New Orléans – newpronounced in English, but Orléans in French. I assure him that in France, we have only Orléans, and that New Orleans is in America. He doubtfully shakes his head, after all, he went there… while I, when did I go for the last time to Orléans?

More Here