Yerevan’s Cascade Memorial to Victims of Repression: Returning from Hilltop Marginalisation

Hans Gutbrod, Arts & Humanities, Ilia State University

Abstract

There is an extraordinary monument to the victims of Soviet-era repressions in a landmark location above Yerevan about which hardly anyone in Armenia knows. On 14 June 2022, a handful of activists gathered at this Cascade Memorial to pay their respects in a moving event. Fitting as that event was, it had limited reach. Fewer than thirty people attended, illustrating how marginalised the history of Soviet repression remains in public engagement. An Ethics of Political Commemoration can help to reconceptualize this approach to commemoration. With a focus on the Cascade Memorial and the memorial day of June 14, Armenians, led and supported by memorial activists, could make this outstanding location come more alive. Linking visits to the experience of being part of a larger chain of evoking the names of victims is another strategy. In addition, researchers could contribute more insight and document their findings through Wikipedia. This effort could highlight the challenges of the authoritarian legacy in the country and, perhaps, also contribute to a more civil tone as Armenia moves towards more democracy amidst geopolitical uncertainty. This article also shows the viability of the Ethics of Political Commemoration as an ethical framework for reflecting on questions of remembrance.

Keywords Armenia, Soviet Union, commemoration, history, ethics, Yerevan

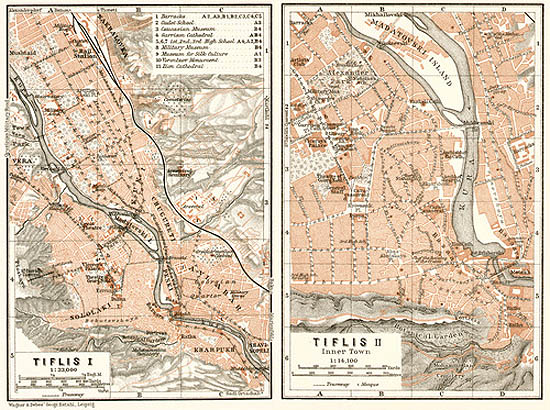

“Everyone in Armenia knows the Cascade complex — a landmark stairway that connects Yerevan’s downtown centre with Victory Park above the city. Five terraces at various levels offer views over Yerevan’s streets and across, to Mount Ararat. Nestled inside the complex is an art museum with event halls served by elevators and escalators. The Cascade’s broad limestone band, over 300 meters long and 50 meters wide, also marks the city’s main north-south axis that runs through the pedestrian Northern Avenue and the imposing opera theatre, the focal point of Yerevan’s cultural scene. Practically every visitor to Armenia’s capital will drop by the garden courtyard at the base of the Cascade, with its cafés, restaurants, and sculptures. Yet hardly anyone in Yerevan knows that the Cascade also contains a major memorial to the victims of Soviet repression on its very top terrace. Like the history of the Soviet repressions itself, this Cascade Memorial remains largely neglected, while aspects of Armenia’s authoritarian past continue to haunt its often-confrontational politics. A handful of Armenians are now trying to restore and recover the memory of the repressions. They see proper commemoration as a step Armenians must take on their path to democracy. Individual victims feature prominently in their remembrance. With the remarkable Cascade Memorial already in place, they have a chance to engage a broader audience in the country, as a visit to their annual commemoration ceremony suggests. This article describes the Armenian commemoration of the victims of Soviet repression from the perspective of participant observation; puts commemoration into the context of Yerevan’s charismatic architecture; applies the Ethics of Political Commemoration to review the practices and suggest some tweaks to overcome marginalisation; and situates this particular commemoration amidst the calls – also from academics – for wider engagement with the past. It also highlights how fragmented knowledge around the Soviet repressions and the creation of the Cascade Memorial is, draws out implications for some state institutions and universities, and connects the commemoration to Armenia’s current political context.”