Conceptual Perspectives to Parallel the Eliava Pictures

Meaning is context-bound, but context is boundless.

Jonathan Culler, Literary Theory, 1997: 91

CONCEPTUAL PERSPECTIVES

*Critical Urban Studies and Planetary Urbanization

*Challenges of Ethnographic Studies of/at Local-Level Sites of Planetary Urbanization

*Conceptual Frameworks of Production of Space and Im/Mobilities

*The Larger Context of Capital’s (Im/)Mobility

*David Harvey on Marx and Capital

*Debt/Credit

*Lefebvre and Production of Space

*David Harvey on Space

*Schmid on Lefebvre’s Dialectic and Production of Space and Its Significance for Ethnographic Fieldwork

*Embodiment and Production of Space

*Gendered Space

*Space and Place

*Heterotopia

Critical Urban Studies

I aim to carry out a theoretically informed (here, mostly visual) ethnographic study. The idea is to look for pathways from ethnography of the market to world conditions and back again.

The larger general theoretical framework for this study is critical urban studies, but with a focus on the daily lives of people at the market.

City Lens(es) and Urban Ideologies

“(A) persistent ‘city lens’ … remains pervasive … This lens, ground in the context of the 19th-century metropolis, interprets the world through a series of binary associations hung on the basic assumption that the city can be defined against a nonurban outside. I develop John Berger’s (2008 [1972]) idea of ‘ways of seeing’ as a heuristic for understanding this situation and, using the case of nature, show how the city lens encourages practitioners and some scholars to romanticize, anachronize or generalize when confronting signs of the not-city in the urban. I conclude by evaluating the limitations of hybridity as a solution to the problems of the city lens, and by outlining an alternative approach. I advocate for turning this way of seeing into a research object, and argue for the importance of a historical and process-oriented examination of the ongoing use of these categories even as critical urban scholars attempt to move beyond them. I use the idea of ‘ways of seeing’ as a heuristic to explore this situation in the world, to evaluate responses in the discipline, and to elaborate (the) suggestion that a new way of seeing is necessary.” Hillary Angelo, 2016

The larger Eliava market is, mainly, a site for car-parts and house-parts commodities. These commodities have different networks of mobilities related to what is referred to as planetary urbanization. These commodities are produced in the context of different industries, forms of ownership, modes of production, and geographies. Labor, as a form of commodity, is aksi offered for exchange at the market.

“The “city” has become a major focal point–both a site and a stake–of intense social, political and ecological struggles. Such struggles are powerfully mediated through urban ideologies that attempt to naturalize or normalize the profoundly unequal power relations and destructive socio-ecological arrangements upon which everyday city life and worldwide urbanization processes are grounded. One of the key tasks of critical urban theory is to illuminate the origins, operations, and implications of such ideologies and, in so doing, to help construct alternative vocabularies and cartographies that might facilitate new forms of urbanism based upon radical-democratic empowerment, sociospatial justice, and ecological rationality. This lecture surveys the role of urban ideologies in contemporary capitalism and outlines various ways in which the methodological orientations, historical-geographical metanarratives and normative-political agendas of critical urban theory might destabilize and transcend them.”

Neil Brenner, Urban Ideologies and the Critique of Neoliberal Urbanization – videoed talk

“New forms of urbanization are unfolding around the world that challenge inherited conceptions of the urban as a fixed, bounded and universally generalizable settlement type. Meanwhile, debates on the urban question continue to proliferate and intensify within the social sciences, the planning and design disciplines, and in everyday political struggles. Against this background, this paper revisits the question of the epistemology of the urban: through what categories, methods, and cartographies should urban life be understood? After surveying some of the major contemporary mainstream and critical responses to this question, we argue for a radical rethinking of inherited epistemological assumptions regarding the urban and urbanization. Building upon reflexive approaches to critical social theory and our own ongoing research on planetary urbanization, we present a new epistemology of the urban in a series of seven theses. This epistemological framework is intended to clarify the intellectual and political stakes of contemporary debates on the urban question and to offer an analytical basis for deciphering the rapidly changing geographies of urbanization and urban struggle under early 21st-century capitalism. Our arguments are intended to ignite and advance further debate on the epistemological foundations for critical urban theory and practice today.”

- The urban and urbanization are theoretical categories, not empirical objects.

- The urban is a process, not a universal form, settlement type or bounded unit.

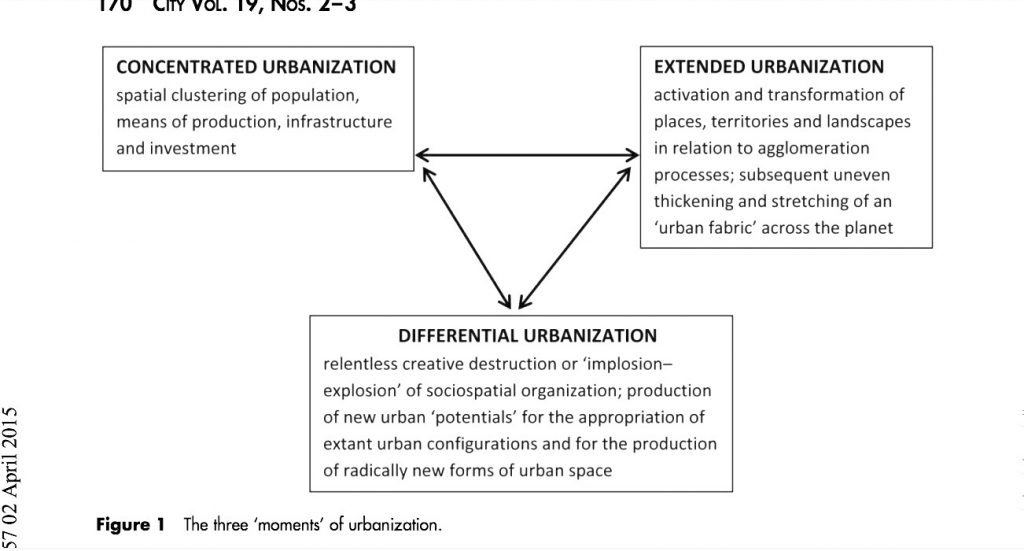

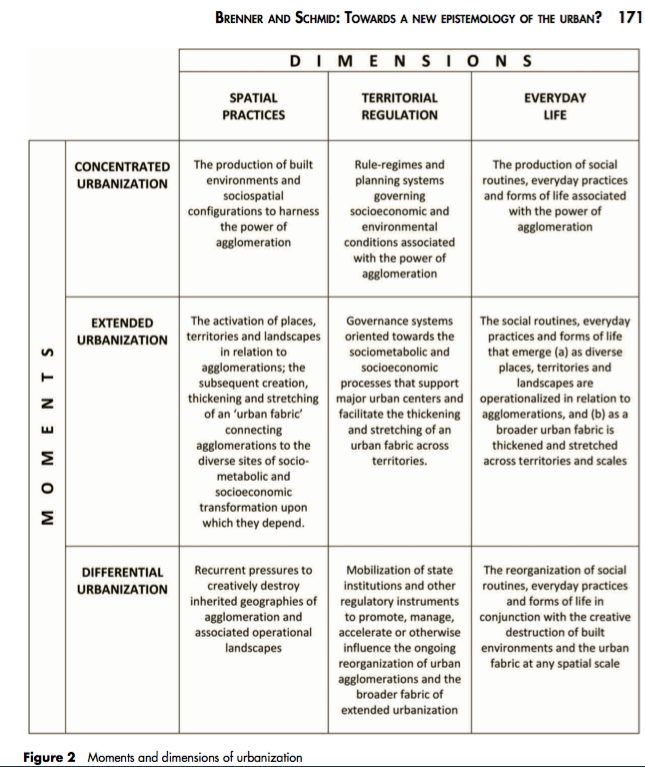

- Urbanization involves three mutually constitutive moments—concentrated urbanization, extended urbanization, and differential urbanization.

- The fabric of urbanization is multi-dimensional.

- Urbanization has become planetary.

- Urbanization unfolds through variegated patterns and pathways of uneven spatial development.

- The urban is a collective project in which the potentials generated through urbanization are appropriated and contested.

Brenner and Christian Schmid, Towards a new epistemology of the Urban, 2015

In the two figures above, different aspects of everyday life, and their larger context of urbanization are pertinent for doing ethnographic fieldwork.

The planetary urbanization theoretical/epistemological framework has been criticized by a variety of people based on post-colonial, critical race-theory, feminist, and queer frameworks.

Debating Planetary Urbanization – Engaged Pluralism

Neil Brenner has provided an article to engage with some of the criticisms (based on the idea of engaged pluralism) and has come up with a series of research questions (summarized below).

“This essay reflects on recent debates around planetary urbanization, many of which have been articulated through strikingly dismissive caricatures of the core epistemological orientations, conceptual proposals, methodological tactics and substantive arguments that underpin this emergent approach to the urban question. Following brief consideration of some of the most prevalent misrepresentations of this work, I build upon the concept of “engaged pluralism” to suggest more productive possibilities for dialogue among critical urban researchers whose agendas are too often viewed as incommensurable or antagonistic rather than as interconnected and, potentially, allied.

The essay concludes by outlining nine research questions whose more sustained exploration could more productively connect studies of planetary urbanization to several fruitful lines of inquiry associated with postcolonial, feminist and queer-theoretical strands of urban studies. While questions of positionality necessarily lie at the heart of any critical approach to urban theory and research, so too does the search for intellectual and political common ground that might help orient, animate and advance the shared, if constitutively heterodox, project(s) of critical urban studies.”

Engaged Pluralism – Nine Research Questions

1) “In what ways might the investigation of planetary urbanization be productively extended and transformed through a more sustained engagement with the knowledge-claims of those in nondominant, subordinate, marginalized, or subaltern positions, in and outside the academy?”

2) “In what ways are contemporary urban ideologies infused with and animated by sexist, racialized, heteronormative, heteropatriarchal, biopolitical, and neocolonial projects of sociospatial transformation? In what ways might our historical genealogy and critique of contemporary “urban age” discourses and practices be productively extended and transformed through the deployment of feminist, queer-theoretical, postcolonial, decolonial, and critical race-theoretical modes of analysis?”

3) “In what ways might our critique of city-centric and city-dominant approaches to the urban question be extended or transformed through a more sustained engagement with earlier feminist and queer-theoretical deconstructions of “heteronormativity” and associated geographical dualisms, including the classic triad of urban/suburban/rural? How might such critiques be extended and transformed through their articulation to postcolonial and decolonial critiques of Eurocentric, metrocentric knowledge-formations, and associated spatial dualisms, such as Occident/Orient, modern/traditional, and culture/nature?”

4) “To what degree does a theoretical focus on capitalist structurations of the urban inhibit, warp, or block engagement with questions of “difference”—whether of gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity, nationality, religion, citizenship status, or otherwise? In what ways might an analysis of capital’s uneven, chronically crisis-prone historical geographies productively inform and animate investigations of the shifting territorial landscapes in which social differences are expressed, materialized, contested, and fought out—and vice versa?

5. New conceptualizations of the urban question with reference to various emergent sociospatial transformations, within and beyond major metropolitan regions, destabilize inherited urban epistemologies. A closely parallel line of argumentation has been articulated by several postcolonial urban theorists who, likewise, connect many of their specific epistemological proposals to the challenges of deciphering contemporary urban transformations. To what degree do feminist, queer-theoretical, and critical race-theoretical approaches to urban questions likewise ground their proposed concepts and methods in relation to the specific tasks associated with analyzing contemporary or emergent forms of urban restructuring? To what degree do such approaches direct attention to essential dimensions of contemporary urban emergence that our work has neglected? If so, what are the implications of (re)considering the latter for our own epistemological proposals, methodological orientations, and research agendas?

6) “In what ways are the geographies of extended urbanization we have begun to demarcate in our work-related, for instance, to the tendential enclosure, industrialization and infrastructuralization of erstwhile agricultural and extractive hinterlands, emergent landscapes of tourism, logistics and waste management, and new regimes of techno-environmental management—forged through gendered, sexualized, racialized, biopolitical, and neocolonial power relations, and associated projects of normalization? How might more explicitly feminist, queer, critical race-theoretical, decolonial, and postcolonial approaches to such dynamics inform, extend, and transform conceptualizations and investigations of extended urbanization?”

7) “The planetary scale of contemporary urbanization is primarily analyzed with reference to Lefebvre’s notions of generalized urbanization and the “planetarization” of the urban, which focus primarily on the spatiotemporal dynamics, contradictions, and contestations unleashed by capital. In what ways could that conceptualization be complemented, extended, or transformed through a more sustained engagement with alternative understandings of the planetary derived from other traditions of literary, political, cultural, spatial, and ecological theory that speak, for instance, to questions of citizenship, politics, sovereignty, coloniality, world ecology, environmentality, the anthropocene, the capitalocene, the posthuman, the nonhuman, technonature, geoculture, and altermondialite.”

8) “In what sense is planetary urbanization a (bio)political project, one that entails not only new strategies of capital accumulation and new formations of capitalist territorial organization, but new frameworks of territorial regulation, state spatial strategies, modes of racial, and/or sexual normalization, formations of governmentality, biopower, and regimes of subjectivity? To what degree might the analysis of such issues help inform the broader project of repoliticizing debates on the urban question, in and outside the academy, in this putatively “post-political” age?”

9) “In what ways might approaches to planetary urbanization contribute to ongoing struggles to imagine and to construct “alter-urbanizations” —alternative pathways for the production, appropriation, and transformation of space, at once in the spheres of politics, law, social reproduction, ecology, infrastructure, and everyday life? How might the post-capitalist visions of “possible urban worlds” and differential space that pervade be extended and transformed by those oriented towards transcending sexist, heteropatriarchal, racially exclusionary, neoimperial, and neocolonial forms of urbanization?”

Neil Brenner, Debating Planetary Urbanization: for an Engaged Pluralism,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, April 2018.

The above are important research questions, but they do not include typical “anthropological” research questions that help to study the local, but could also move between the global and the local.

Challenges of Ethnographic Studies of Local-Level Sites of Planetary Urbanization

A variety of authors have criticized the urban planetary theory for its lack of appreciation of the social at the local level, that is everyday social practices of ordinary people, at specific geographic sites or locations (or different related sites), under present-day dynamic planetary conditions.

Planetary Urbanization and Viewing Local-level Everyday Fluid Lived Practices

“(T)he interdisciplinearity and the methodological variety of urbanization studies are brilliantly evidenced. But as far as the dynamics of urbanization under capitalism are concerned, it is difficult to find confirmation for the thesis that the urban question should be reconceptualized in terms of implosion/explosion. Its main flaw is that it still doesn’t overcome a way of thinking based on centrality and on agglomerations. Contemporary dispersion involving, beside the spatial dispersal of settlements, the movements of increasingly mobile, mainly pauperized, people, is already bringing up much more fluid ways of life that escape such centralist views and evade “urban” and even “planetary urban” branding. Ways of life that can be grasped only by scaling down the planetary view and reap-praising the dirty, loud, not at all university- or library-like everyday experience.”

Elisa Bertuzzo, Review of Implosions/Explosions, Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization, 2013

Bertuzzo’s application of Lefebvre’s idea of production of space in her study of the city of Dhaka is discussed further below.

Social Ontology of the Urban and Epistemology of Planetary Urbanization

This criticism of planetary urbanization is relevant to doing ethnographic study at the local level (at a site like Eliava):

“Though planetary urbanization stands as an ambitious attempt to describe the contemporary horizons of thought on the urban, we argue that it does not yet cross the threshold to new thinking. We contend that, despite good intentions and enormous effort toward breaking new ground, contemporary writing on planetary urbanization also seems largely to reproduce the terrain it is attempting to rework. As much as a new epistemological framework for the urban is desirable, it can only emerge through a reflexive engagement with questions of social ontology of the urban.

For us a social ontology of the urban emphasizes that it is exactly the everyday struggles of people, of life as it is lived in relation to the urban (and beyond) that will shift the terrain of urban theory. To be sure, Brenner and Schmid (2014) have an ontology of the urban (which deconstructs the ‘fixity’ of the dominant urban ontology based on an epistemological framing of spatial containers) and from which their new epistemology arises. However, we argue that this addresses the spatial at the expense of the social.”

Sue Ruddick, Linda Peake, Gökbörü S Tanyildiz, Darren Patrick 2017 Planetary Urbanization: An Urban theory for Our Time?

The theorists of planetary urbanization, specially Brenner and Schmidt, are highly influenced by Lefebvre’s ideas and have helped to promote them in English. As discussed below, Lefebvre’s ideas help seeing the local and the planetary through lived social practices of the people at Eliava.

Conceptual Frameworks of Production of Space and Im/Mobilities

I – Production of Space – Space as a Process

Eliava is a market, it is a contested (semi-)public space.

Three connected, and sometimes contradictory, set of changing processes and practices are producing and reproducing the market’s space:

1) Capital – as a global process, as value in motion.

2) The State‘s involvement – though flexible and changing, but related to national and municipal politics and class interests. In the last decades, though the neoliberal form of capitalism has dominated the state’s policies and practices, but successive government have treated petty “informal” sellers differently.

3) People as Actors – actions and interactions, or lived social practices by stall and shop owners, mobile sellers, workers, (and customers, though not a subject of primary focus here), as individuals and in groups.

It is in this last part, the people’s practices in production of space at the market, that Lefebvre’s ideas are illuminating, though challenging to apply empirically.

Lela Rekhviashvili has done ethnographic work with street vendors in Tbilisi.

Marketization and the Public-Private Divide Contestations between the State and the Petty Traders over the Access to Public Space in Tbilisi

She “critically examines the reasons behind a decade long contestations between the Georgian government and the petty traders over the access to the public space for commercial use.”

Rekhviashvili relies on ethnographic fieldwork conducted in Tbilisi in 2012 and 2013 with legally operating traders and “illegal” street vendors and “interviews with representatives of the city government and secondary literature on Georgia’s post-revolutionary (2003 “Rose Revolution”) transformation.”

“Bridging the critical literature on the politics of the public space with Polanyi’s theory on commodification of fictitious commodities as a precondition of establishment of a market economy, the author argues that for the Georgian government control of the public space was necessary to pursue neoliberal marketisation policies. These policies required removal of the petty traders from public spaces because the state needed to restrict access to public space and limit its commercial usage to delineate public and private property and allow commodification of the urban land and property. As the commodification intensified and the rent prices started growing and fluctuating, the access to the public space became even more valuable for the petty traders. Therefore, the traders developed subversive tactics undermining the division between public and private space and property.”

“With the change of government in 2012, responsibility for the control of vendors was removed from the city hall supervisors’ unit and returned to the police. With this relative relaxation of control, vendors started reoccupying public spaces, or as Asef Bayat would describe the process, they “silently encroached” (Bayat, 1997) on the sidewalks, parks and territories of nearby metro stations and bazaars. As the city has transformed considerably over the last ten years and overall state enforcement capacity is now higher, it should not be expected that Tbilisi will return to its pre-revolutionary state and experience an uncontrolled expansion of “kiosk” trade. But vendors are slowly, less visibly, but consistently returning and occupying public spaces.”

More on Rekhviashvili’s work on street vendors and the idea of informality further below.

Beside’s Polany’s idea, Rekhviashvili‘s study is based on de Certeau’s startegy/tactic framework.

*****

Production of Space

This study relies on Lefebvre’s production of space framework as one of its theoretical frameworks.

“The core of the theory of the production of space identifies three moments of production:

1) first, material production;

2) second, the production of knowledge; and,

3) third, the production of meaning.

This makes it clear that the subject of Lefebvre’s theory is not “space in itself,” not even the ordering of (material) objects and artifacts “in space.” Space is to be understood in an active sense as an intricate web of relationships that is continuously produced and reproduced. The object of the analysis is, consequently, the active processes of production that take place in time.”

Christian Schmid, Henri Lefebvre’s Theory of the Production of Space: Towards a Three-Dimensional Dialectic, 2008:41

Lefebre’s theory of the production of space has been interpreted variously. Christian Schmid’s interpretation, and critique of some other interpretations, is based on his background in the German school of critical theory and dialectics.

Further below I have included more discussion of this model and its empirical applications.

A reflexive take on the use of photography and other visual methods in studying the production of space is or should also be put into sight.

Production of space in relation to im/mobilities at the market is the major focus or question of this study.

II -The Mobilities/Immobilities Framework

“(T)wo years earning a living as a taxi driver in Paris (an experience which deeply affected his (Lefebvre’s) thinking about the nature of space and urban life, kept him from any temptation to an ivory-tower conception of philosophical work.”

David Harvey, Afterword to Production of Space, 1991:426

I have organized the pictures with a mobility/immobility framework in mind.

As the text below indicates, the (im)mobility framework has its advantages and challenges:

Mimi Sheller – Mobilities Turn

“(S)patial theory has deeper roots that begin in theorizations of the production of space in the 1980s, and the emergence of relational understandings of space and spatial processes in the 1990s that led directly into the emergence of the new mobilities paradigm around the turn of the millennium. However, the mobilities paradigm departs from this earlier tradition in part because of its far more transdisciplinary emphasis on cultural mobilities, meaning, representation, affect, and embodied social practices as much as the large-scale political and economic geographies that were the focus of the spatial turn. This means that it has found intersections with many other disciplines and a wide range of epistemological approaches.”

“(T)he new mobilities paradigm furthered the spatial turn in the social sciences in many crucial ways because of the ways in which it called for new methodologies and generated novel multidisciplinary assemblages of empirical and applied research, and even a move towards artistic research creation. The new mobilities paradigm continues to stand in contrast to the quantified empiricist traditions in American and British social sciences, the hierarchies of academic departments, and their disciplinary closure. It also stands against the market-driven discipline of the neoliberal university. Yet it still offers a useful, transformative, and powerful set of questions and methodologies for a dynamic and international research community.”

“(L)ike the spatial turn, the new mobilities paradigm challenged the idea of space as a container for social processes, and thus brought the dynamic, ongoing production of space into social theory across many different domains of research. But beyond that it did something more: it also challenged disciplinary containers and allowed sociologists, geographers, anthropologists, media studies scholars, artists and architects, and many others to move with each other in new assemblages that drew in ever-widening circles of interest, intervention, and creative instigation. The categories of separate social science sub-fields and disciplines were destabilized, put into motion, and the new mobilities paradigm spiraled outward, gathering and making possible these broader shifts.”

The New Mobilities Paradigm

“What ways of thinking and researching space did this new paradigm involve?”

1) “First, it involves examining the place of movement within the very workings of social institutions and of social practices, those institutions and practices that form people’s lives. They each presuppose multiple, interdependent mobilities. Social relationships involve diverse connections, sometimes at a distance sometimes face-to-face. Mobilities depend on multiple kinds of material objects, as well as lumpy, fragile, aged, gendered, racialised, and more or less impaired bodies, inhabited as people are intermittently on the move. In this respect it is built upon the insights of Lefebvre (1991 [1974]) and Massey (2005) (For Space), on the production of space.”

2) “Second, work within the new paradigm examines five different modes of mobilities and their complex combinations that together make possible the institutions and practices of social life and its spatial practices.”

“According to Urry (2007) these are: corporeal travel of people for work, leisure, family life, pleasure, migration, and escape, organized in terms of contrasting time–space patterns (ranging from daily commuting to once-in-a-lifetime exile); physical movement of objects to producers, consumers, and retailers; as well as sending and receiving presents and souvenirs; imaginative travel effected through the images of places and peoples appearing on and moving across multiple print, visual, and social media; virtual travel often in real time transcending geographical and social distance using digital media and communicational connectivity; and communicative travel through person-to-person messages via texts, letters, telegraph, telephone, fax, mobile, and smartphone. Social institutions and practices presuppose some combination of these mobility forms (Urry, 2007).”

3) “Third, these multiple mobilities necessitate distinct exemplars of research to capture and represent various kinds of movement and related spatial practices and mobility regimes. Mobile methods are qualitative, quantitative, visual, and experimental. Some mobile methods that have been recently deployed include walk-alongs , ride-alongs, longitudinal studies of migrants, shadowing, virtual ethnographies, mobile positioning studies, visual studies of digital images, studies of stillness and waiting, social network analysis, biosensing of emotions on the move, and various kinds of textual, sound and visual diaries that respondents keep while ‘on the move’.

All of the above methods offer entirely new perspectives on the broader political and economic power geometries that the original theorists of the spatial turn emphasized, offering data that are more small-scale, more intimate, more interpersonal, and more enacted in everyday relations.”

4) “Fourth, there is a complex assembly of movements and moorings within these mobility forms. Mobilities are organized in and through systems and such mobility systems presuppose ‘immobile infrastructures’ that are increasingly ‘splintered’ in terms of access. Such mobility systems are normally based upon various ‘designs’ that have the effect of circulating people, objects, and information at various spatial ranges and speeds. But these designed mobility systems and routeways can often persist over time. This can be especially seen in the case of the interdependent socio-material systems involved in the automobility system of private vehicles, roads, drivers, passengers, petrol stations, oil drilling, refining, car cultures, and forms of governance. Such mobility systems of course had important spatial implications for cities, suburbs, and the overall inter-regional transportation system that contributed to the uneven development of capitalist spatiality. This is perhaps where the mobilities turn intersects most closely with earlier studies of shifting power geometries and scalar processes. But their effects were not only on built space, but to use Lefebvre’s terms also on conceived space and perceived spaces of representation, and on the lived experiences of the social practice of space.”

5) “Fifth, this paradigm emphasizes how social practices can emerge through ‘unintended consequences’ stemming from the ways people use, innovate, and combine different systems (and their spatialities).”

6) “Finally, the world is not simply more mobile than ever, at least not in the sense of there being an enhanced ‘freedom of mobility’. Mobilities are tracked, controlled, governed, under surveillance and unequal, especially because of the increasing power of big ‘mobile’ data. Mobility is relative with different historical contexts being organized through specific constellations of uneven mobilities. These may produce relational effects of heightened intensification of mobility and speed for some relative to others, but there is also a record of coerced mobilities, displacement, and closely controlled tracking, which counters discourses of ‘mobility as freedom’.”

Mimi Sheller, From Spatial Turn to Mobilities Turn, Current Sociology, 2017: 1–17

“Mobilities research has instigated a creative recombination of existing theoretical traditions, methodological approaches, epistemologies, and even ontologies of a world constituted by relations rather than entities, which is why it is sometimes referred to as a ‘new mobilities paradigm’ (Sheller and Urry, The New Mobilities Paradigm, 2006).”

“It combines social, spatial, and critical theory in new ways, and in so doing has provided a transformative nexus for bridging micro-interactional research on the phenomenology of embodiment, the cultural turn and hermeneutics, postcolonial and feminist theory, macro-structural approaches to the state, political-economy and globalization, and elements of science and technology studies (STS), communication, media and software studies.”

“(T)here has been an explosion of research on mobility systems and their practices, meanings and power relations, as seen not only in the journal Mobilities, but also the new journal Transfers: Interdisciplinary Journal of Mobility Studies. Encompassing not only human mobility, but also the mobility of objects, information, images, and capital, mobilities research includes study of the infrastructures, vehicles, and software systems that enable physical travel and mobile communication to take place at many different scales simultaneously. Mobilities research thus promotes interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary study, requiring multiple methods that can address the intertwined practices of many different kinds of contemporary (im)mobilities at a variety of scales and speeds.”

Mimi Sheller, The New Mobilities Paradigm for a Live Sociology, Current Sociology Review, 2014: 1-23

Combining the Spatial and Mobilities Turns

The main research questions are about the daily lives of the people at the market, processes related to production of space at the market and im/mobilities of various kinds.

Choice of research questions, epistemologies, methodologies, and methodological procedures should be adapted to include points of interest of future research team members.

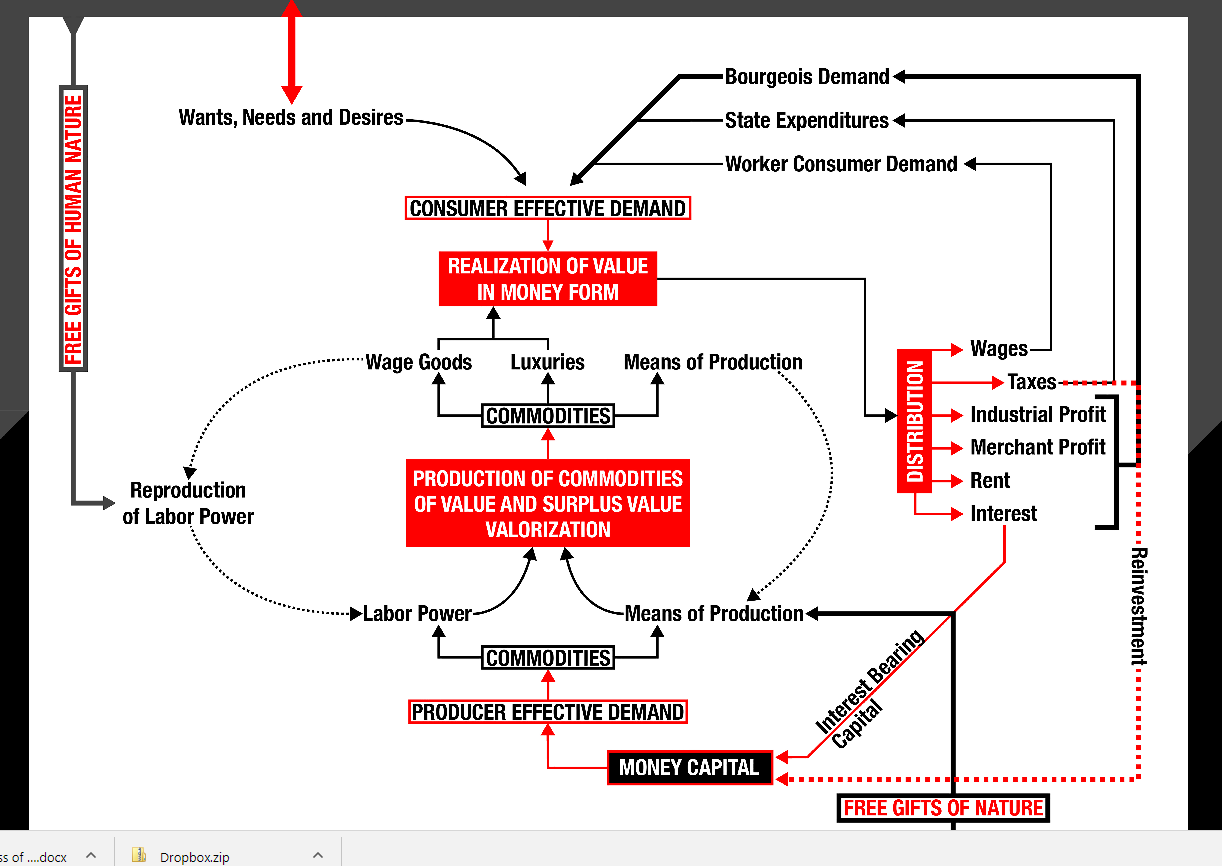

The Larger Context of Capital’s (Im/)Mobility

“Capital is not a thing, but rather a process that exists only in motion. When circulation stops, value disappears and the whole system comes tumbling down.”

A Companion to Marx’s Capital, 2010:14

Harvey’s discussions of global capitalism provide a general framework for studying Eliava. His interest in the processes of capital’s global mobility, and emphasis on urbanization, realization of value in money form, distribution, rent, as well as his stress on debt/finance and space (or space/time) in capital’s mobility processes are proposed to rely upon for contextualizing what is seen at Eliava.

“I would put finance capital up in front, if I were Marx.”

David Harvey

Reading Marx’s Capital with David Harvey

Visualizing Capital’s Im/Mobilities

David Harvey – Marx and Capital: The Concept, The Book, The History

- CAPITAL AS VALUE IN MOTION

- VALUE AND ANTI-VALUE

- VALUE AND ITS MONETARY EXPRESSION

- THE SPACE AND TIME OF VALUE

- USE VALUES: THE PRODUCTION OF WANTS, NEEDS AND DESIRES

- BAD INFINITY AND THE MADNESS OF ECONOMIC REASON

Lefebvre: Production of Space

“The space of a (social) order is hidden in the order of space…. How is this possible? How could such capabilities, such efficacy, such ‘reality’ lie hidden within abstraction? To this pressing question here is an answer whose truth has yet to be demonstrated: there is a violence intrinsic to abstraction, and to abstraction’s practical (social) use” Lefebvre, The Production of Space, 1991:289

Reading Lefebvre- Stuart Elden

“(M)any people, especially in Geography, go to The Production of Space. That’s a major work, certainly, but I don’t think it’s a good place to start. It’s a difficult book, which was Lefebvre’s writing up – the theoretical culmination – of several years working on urban and, earlier, rural questions. All-too-often it is read through the lens of the first chapter – a broad, conceptual schema – and not balanced by the much more historical study found in later chapters. I’ve heard several people say that this was the first, and last, thing of Lefebvre they read, or started to read. Any serious engagement with Lefebvre has to come to terms with this book, but it’s not a good place to start. The Critique of Everyday Life is another way in. The books of that series – three volumes from 1947 to 1982, and his last book Elements of Rhythmanalysis, which he saw as an informal fourth volume. I think Everyday Life in the Modern World is the best single place to go for this aspect of his work. Writings on Cities (which includes The Right to the City and various other pieces) and The Urban Revolution are good places to start.”

Online Sources by Lefebvre:

State, Space, World, Selected Essays, 2009

“(Social) space is a (social) product; in order to understand this fundamental thesis it is necessary, first of all, to break with the widespread understanding of space imagined as an independent material reality existing “in itself.”

“Against such a view, Lefebvre, using the concept of the production of space, posits a theory that understands space as fundamentally bound up with social reality. It follows that space “in itself” can never serve as an epistemological starting position. Space does not exist “in itself”; it is produced.”

Christian Schmid – The Trouble with Henri: Urban Research and the Theory of the Production of Space. In: Stanek, Łukasz / Schmid, Christian / Moravánsky, Ákos (eds.): Urban Revolution Now: Henri Lefebvre in Social Research and Architecture, 2015: 27-48

“Henri Lefebvre’s theory of the production of (urban) space, which he developed over a short period from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, is widely quoted and the subject of intense debates.”

“This process of appropriation and application of Lefebvre’s theory has not been untroubled. Time and again, all sorts of confusions and problems have arisen. While these initially concerned mainly questions of interpretation and theoretical construction, more recent discussions have primarily focused on the question of how this theory can be successfully introduced into empirical analysis.“

A New Turn to Lefebvre’s Work

“For a few years now, a new and different form of access to Lefebvre’s work can be observed. It is marked

1) “first of all by the fact that it relates in a fundamentally different way to Lefebvre’s heterodox and open-ended materialism than earlier interpretations. It no longer tries to demarcate its position from Lefebvre’s epistemology, or conversely to functionalize his work for a specific theoretical approach, but rather to have an independent and open debate on his thinking.”

2) “Second, an informed and intense discussion of the epistemological and historical context of his theory was initiated, together with careful analysis of a wide range of aspects of his complex work.

“This development was much favored by the translation of some of his most important texts into English, which made many aspects of his theory accessible to a broader audience – the lack of translations had long posed almost insurmountable obstacles to the English-language interpretation of his work. Thus, in recent years, it has been possible to clarify many open questions that had caused considerable confusion, especially concerning the construction of his theory.” “Furthermore, after the dominant Lefebvre interpretation had long focused mainly on the question of space, topics such as urbanization and the urban, the state and everyday life found a new or renewed interest.

3) “Third, this reception is characterized by curiosity and an open-minded approach to Lefebvre’s work. An increasing number of texts take Lefebvre’s theory as a point of departure, place it in a contemporary context, and thus make it fruitful for further reflections and analysis.

Among these are efforts to combine Lefebvre’s with other approaches and thus to open up new perspectives.

4) “Fourth, there has been an increasing number of empirical applications. More and more studies are being published that not only cite Lefebvre’s work – such citations have become almost routine in certain fields of research – but integrate his theory into the very heart of the investigation itself.”

“In this way, (this new) wave of Lefebvre interpretation has brought about an important expansion of our horizon: it is rooted in an undogmatic reading, uses Lefebvre’s work as a point of departure for further reflection, and is at the same time more precise and more open than previous phases of reception.“

Elements of a Possible Production of Space Research Strategy

“(A) few elements of a possible research strategy.

1) “First of all, Lefebvre’s theory must be taken seriously if it is to deploy its full potential. It should not be regarded as a quantité négligeable; nor should it be used as a quarry of ideas and concepts. Rather, its principles of construction should be illuminated and the full potential of its effectiveness should be exhausted.

2) “Second, it is crucial to remember that the most important texts on the theory of the production of space were written more than four decades ago, which means that their further development is unavoidable. We live in a completely different world today: new developments have arisen, and we require new concepts to be able to understand the world.”

“It is therefore essential that Lefebvre’s work not be canonized, but continuously expanded in engagement with reality.”

3) “Additionally, theoretical advances that have since been achieved should also be acknowledged and taken into account.

4) “Finally and most importantly, employing Lefebvre’s concepts means applying them, which implies following the core of Lefebvre’s procedure: always confronting the theory with concrete experiences, experimenting, continuously engaging concrete practice in order to develop the theory further, immersing the theory in reality and making it fruitful – and thus ultimately also going beyond Lefebvre.“

Christian Schmid – The Trouble with Henri: Urban Research and the Theory of the Production of Space. In: Stanek, Łukasz / Schmid, Christian / Moravánsky, Ákos (eds.): Urban Revolution Now: Henri Lefebvre in Social Research and Architecture, 2015: 27-48

Lefebvre’s Dialectic and Production of Space

Christian Schmid’s interpretation of Lefebvre’s dialectics is important for studying production of space at a local level, like Eliava. Christian Schmid comes from the (German) Critical Theory background with its emphasis on the dialectical method.

Christian Schmid – HENRI LEFEBVRE’S THEORY OF THE PRODUCTION OF SPACE Towards a Three-Dimensional Dialectic

Lefebvre’s Unique Version of Dialectics – The Three-dimensional Analysis of the Production of Space

“Nowhere are both the problems and the potentialities of Lefebvre’s theory more evident than in his famous three-dimensional conception of the production of space, the key epistemological element of this theory.

(W)hat this conception refers to is not a set of three independent dimensions, but an ensemble of three contradictions and thus interdependencies between three poles.”

“Therefore the goal cannot be to use the three dimensions like drawers to be filled with corresponding empirical examples or as a scaffold that serves to order the abundance of social reality. Rather, it should be understood as an instrument that can be used to actively advance the analysis.”

“Therefore there are the dialectical relationships between the three poles that are of primary interest.”

“The aim must be to regard such relationships as active elements and not to study them independently, but rather to analyse the dialectical interplay of the dimensions.”

“As Lefebvre emphasized, again and again, the three dimensions or moments should be neither conflated nor separated (see, for example, Lefebvre, The Production of Space, 1991 [1974]: 12, 413).”

Lefebvre’s Unique Version of Dialectics

“(T)hree hitherto neglected aspects are crucial to an understanding of Lefebvre’s theory.”

1) “First, a specific concept of dialectics that can be considered as his original contribution. In the course of his extensive oeuvre, Lefebvre developed a version of dialectics that was in every respect original and independent.

It is not binary but triadic, based on the trio of Hegel, Marx, and Nietzsche.”

2) “The second determining factor is language theory.The fact that Lefebvre developed a theory of language of his own while leaning on Nietzsche was hardly ever considered in the reception and interpretation of his works, the linguistic turn notwithstanding. It was here that he also for the first time realized and applied his triadic dialectic concretely.”

3) “The third crucial element is French phenomenology. While Heidegger’s influence on Lefebvre’s work has already been discussed in detail, the contribution of the French phenomenologists Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Gaston Bachelard has, for the most part, not received due consideration. These three neglected aspects could contribute decisively to a better understanding of Lefebvre’s work and to a fuller appreciation of his important and path-breaking theory of the production of space.”

(Schmid, p.28)

“Central to Lefebvre’s materialist theory are human beings in their corporeality and sensuousness, with their sensitivity and imagination, their thinking and their ideologies; human beings who enter into relationships with each other through their activity and practice.”

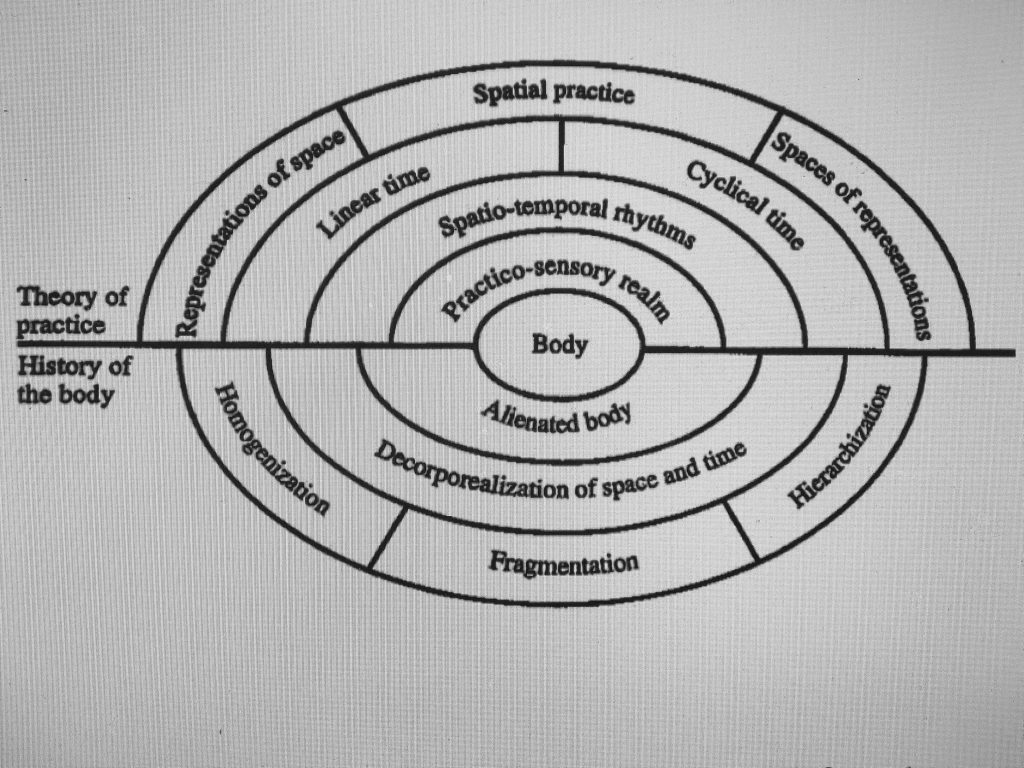

“Lefebvre marks the phenomenological access to the three dimensions of the production of space with the concepts of the perceived (perçu), the conceived (conçu), and the lived (vécu).

This trinity is at once individual and social; it is not only constitutive for the self-production of man but for the self-production of society.

All three concepts denote active and at once individual and social processes.

• Perceived space: space has a perceivable aspect that can be grasped by the senses. This perception constitutes an integral component of every social practice. It comprises everything that presents itself to the senses; not only seeing but hearing, smelling, touching, tasting. This sensuously perceptible aspect of space directly relates to the materiality of the “elements” that constitute “space.”

• Conceived space: space cannot be perceived as such without having been conceived in thought previously. Bringing together the elements to form a “whole” that is Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space then considered or denoted as space presumes an act of thought that is linked to the production of knowledge.

• Lived space: the third dimension of the production of space is the lived experience of space. This dimension denotes the world as it is experienced by human beings in the practice of their everyday life.”

“On this point Lefebvre is unequivocal: the lived, practical experience does not let itself be exhausted through theoretical analysis.

There always remains a surplus, a remainder, an inexpressible and unanalysable but most valuable residue that can be expressed only through artistic means.”

Viewed from a phenomenological perspective, the production of space is thus grounded in a three-dimensionality that is identifiable in every social process.

“Lefebvre demonstrates this by using the example of exchange. Exchange as the historical origin of the commodity society is not limited to the (physical) exchange of objects. It also requires communication, confrontation, comparison, and, therefore, language and discourse, signs and the exchange of signs, thus a mental exchange, so that a material exchange takes place at all. The exchange relationship also contains an affective aspect, an exchange of feeling and passions that, at one and the same time, both unleashes and chains the encounter.”

Christian Schmid, Henri Lefebvre’s Theory of the Production of Space: Towards a Three-Dimensional Dialectic, 2008:27-45

“(E)mpirical studies that fully operate with this three-dimensionality require a huge effort.

They must:

1) First, analyze spatial practice, that is, the material processes related to the production of space.

2) Second, examine the representations of space, that is, discourses, concepts, plans and so on.

3) Third, also integrate into the analysis the spaces of representation and thus lived experience.

That means applying a whole range of often demanding and laborious, mainly qualitative, methods.

4) Fourth, additionally, the dialectical interdependencies between the three dimensions must be analyzed, which is again not an easy task. Nevertheless, it is possible to carry out such analyses, and they can be very fruitful (see, for example, Stanek, Bertuzzo 2009, Schmid 2012).”

Heni Lefebvre Today

Rethinking Theory, Space and Production: Henri Lefebvre Today

“The research project Rethinking Theory, Space and Production: Henri Lefebvre Today embraces the potential of Lefebvre’s theory of production of space in urban research and architecture. This theory opened up new ways of understanding the processes of urbanization, their conditions and consequences at any scale of social reality: from the practices of everyday life to the world-wide flows of people, capital, information and ideas. At the same time, Lefebvre’s theory has the capacity to aggregate urban politics, research and design practices through his exploration of urbanization of an open-ended process, defined as much by its history as by its potentials.”

Christian Schmid – The Trouble with Henri: Urban Research and the Theory of the Production of Space. In: Stanek, Łukasz / Schmid, Christian / Moravánsky, Ákos (eds.): Urban Revolution Now: Henri Lefebvre in Social Research and Architecture, 2015: 27-48

David Harvey on Space

SPACE AS A KEY WORD, David Harvey 2004

Accessibility and Distanciation |

Appropriation and Use of Space |

Domination and Control of Space |

Production of Space |

|

|

|

||||

Material Spatial Practices (experience) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

Representations of Space (perception) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

Spaces of Representation (imagination) |

|

|

|

|

Source (Lefebvre/Harvey Space Grid) – From Watts, Space of Everything, 1992:119

Based on Harvey, The Conditions of Postmodernity, 1989:220-221

“The grid of spatial practices can tell us nothing important by itself. To suppose so would be to accept the idea that there is some universal spatial language independent of spatial practices. Spatial practices derive their efficacy in social life only through the structure of social relations within which they come into play. Under the social relations of capitalism, for example, the spatial practices portrayed in the grid become imbued with class meanings.” 1989:222-23

This dissertation was later turned into a book:

Fragmented Dhaka: Analysing Everyday Life with Hernri Lefebvre’s Theory of Production of Space, 2009

“(Lefebvre’s) work will first be contextualised within the pertinent philosophical traditions and movements; secondly, his theory of the production of space will be illustrated and, thirdly, critically arranged for the envisaged research.”

Embodiment and Production of Space

Embodied Im/Mobilities

“Bodies – deployments of energy – produce space and produce themselves, along with their motions, according to the laws of space.”

Lefebvre, The Production of Space, 1991:17

“Western philosophy has betrayed the body; it has actively participated in the great process of metaphorization that has abandoned the body; and it has denied the body. The living body, being at once ‘subject’ and ‘object’, cannot tolerate such conceptual division, and consequently philosophical concepts fall into the category of the ‘sign of non-body.”

Lefebvre, The Production of Space, 1991: 407

Kristen Simsonsen, Bodies, Sensations, Space, and Time: The Contribution from Henri Lefebvre, 2005: 1-14

“(I)t may be interesting to relate Lefebvre’s formulations to a rather dominant tendency in social discussions on the body – a theoretical distinction that is often attributed to the work of Merleau-Ponty and Foucault (Crosley, 1996). On one side of the line stand analyses of the active role of the body in social life, of the body as lived and generative, and on the other side are studies of the body as acted upon, as socially and historically constructed and inscribed from the outside. The interesting point about Lefebvre’s discussion of the body is that he transcends this division, and that the means of this transcendence is the production of space.”

“(Below), I attempt in a very simple manner to illustrate the two sides of Lefebvre’s conjunction of body, space and time.”

“The upper part of the figure represents the discussion primarily conducted in this essay. It is about the generative and creative social body, as it would be represented in a theory of practice. As part of the lived experience, the body constitutes a practico-sensory realm that is performed in the spatio-temporal rhythms of everyday life. In these rhythms, constituting and constituted, different modalities of social spatiality and social temporality are incorporated, as cyclical and linear repetitions, and as the conjunction of the perceived, the conceived and the lived.

In the lower part of the figure, Lefebvre’s common interest with Foucault in power and the history of the body is represented. To Lefebvre, this is about the above-mentioned history of increasing abstraction, of the decorporealization of space and time. For both space and time (and the body), Lefebvre describes this process of abstraction as simultaneously one of homogenization, fragmentation and hierarchization. This history differs from the one given by Foucault because of its basis in the production of space. Here too Lefebvre treats space as both producing and a product of the human body, as a perception and a conception, not simply the imposition of a concept, or a space, upon the body.”

“In the intersection between Lefebvre’s social ontology of the body and his history of the body, the body turns into a critical figure – a site of resistance and active struggle”

“Thanks to its sensory organs, from the sense of smell and from sexuality to sight … the body tends to behave as a differential field. It behaves, in other words, as a total body, breaking out of the temporal and spatial shell developed in response to labour”

Lefebvre, 1991: 384 – quoted by Kristen Simsonsen

“This means that the body, as a producer of difference (through rhythms, gestures, imagination), has an inherent right to difference, formulated against forces of homogenization, fragmentation, and the hierarchical organized power.

Lefebvre located these struggles for the right to be different at many scales, but at the scale of the body two aspects are crucial. One is the ‘Festival’, as the site of participation and of the possibility of the poesis of creating new situations from desire and enjoyment. The other is sexuality, involving struggles of relations between the sexes (a feminine revolt) as well as relations between sexuality and society.”

Kristen Simsonsen, Bodies, Sensations, Space, and Time: The Contribution from Henri Lefebvre, 2005: 11

Research Question: Could we look at times of GeoAir artists’ involvement, as well as moments of playing boardgames as times of embodied enjoyment?

The Visual

Could the fragmented and abstract characteristic of photographic images capture lived social practices?

“We are concerned with practical and social activities which are supposed to signify or ‘show’ the truth, but which actually comminute space and ‘show’ nothing besides the deceptive fragments thus produced. The claim is that space can be shown by means of space itself.

Such a procedure (also known as tautology) uses and abuses a familiar technique that is indeed as easy to abuse as it is to use – namely, a shift from the part to the whole: metonymy.

Take images, for example: photographs, advertisements, films. Can images of this kind really be expected to expose errors concerning space? Hardly. Where there is error or illusion, the image is more likely to secrete it and reinforce it than to reveal it. No matter how ‘beautiful’ they may be, such images belong to an incriminated ‘medium’. Where the error consists in a segmentation of space, moreover – and where the illusion consists in the failure to perceive this dismemberment- there is simply no possibility of any image rectifying the mistake.

On the contrary, images fragment; they are themselves fragments of space. Cutting things up and rearranging them, decoupage and montage – these are the alpha and omega of the art of image-making.

As for error and illusion, they reside already in the artist’s eye and gaze, in the photographer’s lens, in the draftsman’s pencil and on his blank sheet of paper. Error insinuates itself into the very objects that the artist discerns, as into the sets of objects that he selects. Wherever there is illusion, the optical and visual world plays an integral and integrative, active and passive, part in it. It fetishizes abstraction and imposes it as the norm. It detaches the pure form from its impure content – from lived time, everyday time, and from bodies with their opacity and solidity, their warmth, their life and their death. After its fashion, the image kills. In this it is like all signs.

Occasionally, however, an artist’s tenderness or cruelty transgresses the limits of the image. Something else altogether may then emerge, a truth and a reality answering to criteria quite different from those of exactitude, clarity, readability and plasticity. If this is true of images, moreover, it must apply equally well to sounds, to words, to bricks and mortar, and indeed to signs in general.”

Lefebvre, The Production of Space, 1991:96-97

“In a footnote to this comment, Lefebvre mentions a photographic feature by Henri Cartier-Bresson in Politique-Hebdo on June 29th 1972. Since Cartier-Bresson was visiting the Soviet Union during this period, Lefebvre is probably referring to the photographic reportage he made there in 1972. What is it that made these photographs so uncommon, that they could be seen as an exception to Lefebvre’s rule that photography fragments reality? Certainly not their “exactitude, clarity, readability and plasticity,” as these are all characteristics of the fragmenting tendency of photography in Lefebvre’s view. It is most probably the way they relate to the daily lives of the people that are portrayed and the fact that the images can be seen as a social commentary on the social conditions of people living in the Soviet Union in the 1970’s. Furthermore, the photographs from 1972 were shown in Politique-Hebdo next to earlier photographs of the Soviet Union, made by Cartier-Bresson in 1954, thus showing how the social conditions of these people changed over the course of 20 years. They portray reality as a process and thereby respect it in its dynamic nature.”

Bram Van Beek, Production of Place: A Photographic Topoanalysis, 2018: 24

Henri Cartier-Bresson Soviet Union 1954 Pictures

Henri Cartier-Bresson Soviet Union – Armenia – 1972 Pictures

Henri Cartier-Bresson Soviet Union – Georgia – 1972 Pictures

Henri Cartier-Bresson Soviet Union 1972 – Russia – Pictures

Henri Cartier-Bresson Russia 1973 Pictures

Eliava, as a small site, juxtaposes and mixes materialities, memories, and living generations of the Soviet times with those of the post-Soviet times, and presents how the conditions have changover time. Thus, the Eliava images of shared below, and the framework discussed, may help to bypass, partially, some of the criticisms Lefebvre has for forms of visuality that cannot capture the lived practices of producing space.

But, participatory, art-based research on the daily lived practices of people at Eliava in the future could overcome these criticisms to some degree more.

Strategy and Tactic

“A tactic is a calculated action determined by the absence of a proper locus […]. The space of a tactic is the space of the other. Thus, it must play on and with a terrain imposed on it and organized by the law of a foreign power […] it is a maneuver ‘within the enemy’s field of vision’”

de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, 1984: 37

“The case of Georgian street vendors indicates the limits on both the strategies of the state and the tactics of the vendors. On the one hand, even if vendors’ tactics were subversive and could be understood as resistance or a countermovement to marketisation in the Polanyian sense, they were nevertheless, as Certeau reminds us, manoeuvres “within the enemy’s field of vision” (Certeau, 1984, p. 37). Hence, it was the government’s strategy to discourage the mobilisation of vendors and make them more and more invisible, while vendors tried to use their invisibility to their own advantage as far as possible. Despite their diverse and creative approaches to manoeuvring in the space delimited for them, invisibility and silencing only enhanced the social and economic vulnerability of the vendors. On the other hand, this struggle also underlines the limits to the exclusive strategies of those in power. As long as access to public space continues to be crucial for the income generating activities of numerous socially vulnerable individuals and households left without social support, these groups and individuals will continue to subvert state regulations and the imperative of marketisation through their daily practices. The slow recovery and revival of illegal street vending in Tbilisi since the change of government only confirms that spontaneous resistance will not fade away as long as the neoliberal marketisation process deepens and institutions for social protection remain non-institutionalised.”

Lela Rekhviashvili, Marketization and the Public-Private Divide Contestations between the State and the Petty Traders over the Access to Public Space in Tbilisi, 2015: 491

Space and Place

Andy Merrifield – Henry Lefebvre: A Critical Introduction, 2006

Chapter 6 – Space

Place and Space: A Lefebvrian Reconciliation, 1993

Michel de Certeau’ and Henri Lefebvre

Timotheus Vermeulen, Space is the Place, 2015

” It’s fair to say that, by and large, contemporary discussions of space and place have their roots in two distinct strands of thought: Michel de Certeau’s post-structuralist theory of space as a ‘practiced place’ and Henri Lefebvre’s dialectically materialist conceptualization of place as a moment in and of space.”

shtick is to read the environment as one would a script: that is, like written speech. He argues that place is to space ‘like the word when it is spoken’. What he means by this is that, when city planners map out a city, they envisage places, points on the grid. These are locations, nodes, corners and roads.”

“These places, these points on the grid, De Certeau suggests, are like a language’s grammar or the letters of the alphabet. What he calls space is what happens when dwellers navigate those places: that is, when we put the individual letters together, when we formulate sentences, when we articulate words. Hence, one of De Certeau’s most cited lines: ‘Space is a practiced place.’ Space, here, is always spatialization: the putting to action or – to use that post-structuralist term – the performance of a pre-existing script.”

“In De Certeau’s hierarchical definition, place is thus the stable, static, ideologically informed given, whereas space is about potentially anarchic movement.”

“In contrast to De Certeau, Lefebvre did not understand space linguistically, at least not exclusively. Our environment, he asserts in his 1970 response to the disappointments of May 1968, The Urban Revolution, may resemble a language, a sign system, but cannot, and should not, be reduced to it. Semiology may therefore be drawn upon when studying space, but should always be applied in relation to other models of analysis, foremost among them phenomenology and social theory.”

“In his 1974 magnum opus The Production of Space, Lefebvre theorizes space as a trialectic (a triple dialectic) between three different forces. The first force is what he calls ‘conceived space’: the power play of capital and state, i.e. the investments of bankers, the rules of bureaucrats, the blueprints of architects. The second force is ‘lived space’: the desires of the dwellers, their dreams and memories. The third force, finally, is ‘perceived space’: the way in which these dwellers actually use space. In other words, what Lefebvre calls space is the dynamic between top-down plans, bottom-up experience and the negotiation between them. Just as in Marx’s dialectic, in which thesis meets its antithesis, in Lefebvre’s picture of space, forces also continuously move into one another, battling each other, subjecting, submitting, sublating and, eventually, turning struggle into synthesis. What Lefebvre calls space, therefore, is characterized by a continuous social dynamic.”

“I imagine that some of the difficulty in clearly defining ‘place’ and ‘space’ stems from this conceptual split. For one tradition – in De Certeau’s vein – space is an inter-subjective activation of a static site, a place; while for another – in Lefebvre’s – place is the momentary suspension of a social flow, i.e. space. It is important, however, that we understand the difference, because our engagement with the world around us hinges on it. For de Certeau, agency resides almost exclusively within space. According to his Foucauldian logic, the only freedom you have is to formulate alternative sentences. For the actor, after all, the script is beyond reach. It’s not his to change: it’s the author’s. If we follow Lefebvre’s conceptualization, however, it is place where the intervention occurs. It is place, after all, where the complex trialectic of space is tangible: it is where we can get our hands on it, where we can latch onto, and potentially intervene in, either of the three flows of space. De Certeau understands agency as the enactment of a script not our own, whereas Lefebvre sees it not as a container for action but as the construction of action itself.”

Timotheus Vermeulen, Space is the Place, 2015

Systemic Edges as Spaces of Conceptual Invisibility

‘The language of more – more inequality, more poverty, more imprisonment, more dead land and dead water, and so on—is insufficient to mark the proliferation of extreme versions of familiar conditions.’

I will argue that we are seeing a proliferation of systemic edges which, once crossed, render these extreme conditions invisible. I will focus on this interplay between extreme moment and the shift from visible to invisible – the capacity of a complex system to generate invisibilities no matter how material the condition.” Saskia Sassen

Author Meets Critics: Brutality and Complexity in the World Economy

This talk is based on Saskia Sassen’s Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity, 2014.

*****

Eliava Heterotopia – Eliava In-Place and Out-of-Place

The Geographies of Heterotopia

“There are no signs that the notion of heterotopia is losing popularity in studies of cultural and social geography, or in various other disciplines.

However, a collection of over twenty essays by mainly architects, planners and urbanists, Heterotopia and the City , also demonstrates a seriously considered range of potentially useful applications.”

Are there any commonalities in the various applications and has the idea anything to offer future research?

Arguments about the potential usefulness of the concept of heterotopia often continue to focus on the question of an ‘alternative’ space. As we have seen, those who attack the idea tend to assume that Foucault is putting forward the possibility of an alternative realm of difference, something completely outside the everyday. However, some of the most convincing re-imaginings of Foucault’s brief accounts adopt a more nuanced approach, concentrating, for example, on spaces that seem to be both mundane and extraordinary, embedding multiple meanings around a set of spatio-temporal contradictions or ambiguities. Such research focuses on a social or cultural space that is both in place and out of place.”

Peter Johnson, The Geographies of Heterotopia

In this study I use the concept of heterotopia for two spaces/times:

a) The board game (played by the market people)

b) The art events at Eliava (by outside artists in relation to/in conjunction with the market people)