What can a person or a group do if they are deprived of voice and the freedom of expression? When they cannot speak up about their problems and raise issues they are concerned about in the public space? When they do not have access to mainstream media to reach wider audiences? When they are oppressed in one way or another or struggle for survival? In other words, how can people cope with structural violence – the systematic harm that can be done through certain social structures and institutions?

For the last few decades, street art has increasingly become a powerful tool for the voice of the oppressed in different parts of the world. People from minority groups, the underprivileged, the marginalized, civic and human rights activists often use it as a means of communication. They create influential images and messages illustrating their concerns and troubles. They trigger discussion about underrepresented or tabooed topics. Often anonymous, street art challenges the dominating public opinion, questioning issues of justice, security, roles in the society, raising the voices of those who are excluded from political decision making and the public space.

Publicity and easy access are both a strength and a weakness for street art. Images or messages are usually placed where people can notice them. For the same reason, they are easily spotted and erased by those who oppose the image or the message. Some of them can “live” for a few hours; others “resist” a few days or weeks. Rarely can street art survive for a few months, especially if it represents “unpopular” views. It is impossible to predict the exact “life cycle” of street art. It is frequently erased, broken, deleted, painted over, and dissolved.

For the past decade, the South Caucasus societies have also seen a surge of street art-ctivism. Groups and individuals have used it as an alternative way of public speaking. They have raised and protested issues ranging from unfair socio-political processes to specific cases of oppression, injustice, and violence.

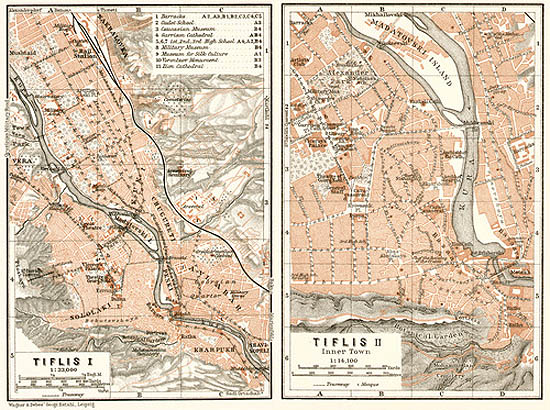

In this piece, we present selected works of street art – street artwork – in Armenia and Georgia. Most of them do not exist anymore. They have been subject to official or unofficial “censorship” and “cleaning”. The photographs were taken in different cities of Georgia and Armenia and depict deeply embedded issues in these societies. Some of these pieces have common topics and address the same issues in both societies. Others are related to country-specific issues. These artworks belong to brave art-ctivists who deliver “unsanctioned” images and messages to the public space, raise the silenced voices in their societies, and strive for changes in their communities. They “speak” about people’s feelings and attitudes and can, therefore, contain commonly used language, including swear words and other kinds of expressive language.

This 2015 piece of street art in Yerevan tells you that street art-ctivism is “A Method to Struggle”. The artist’s pseudonym is Hakaharvats meaning “counterblast”.

“A Method to Struggle”. Artist: Hakaharvats. Location: Koghbatsi Street, Yerevan, Armenia. Photo Credits: Aren Melikyan. Date of the Photo: 2015.

Common Topics in Georgian and Armenian Street Art

Against Political Oppression, Regimes, and Surveillance

George Orwell’s famous dystopian book “1984” describes a system where everyone is under the strict control and surveillance of the state. “Thinkpol” – the Thought Police – identifies and punishes Thought Criminals – those who have the capacity of independent thought. There is no space for real freedom in Oceania. Screens and informers are everywhere. Thinkpol immediately eradicates any alternative to the official version of reality. Only one political party is entitled to set rules, take office, and make political decisions. There is no real freedom of choice, democracy, and public will in Oceania.

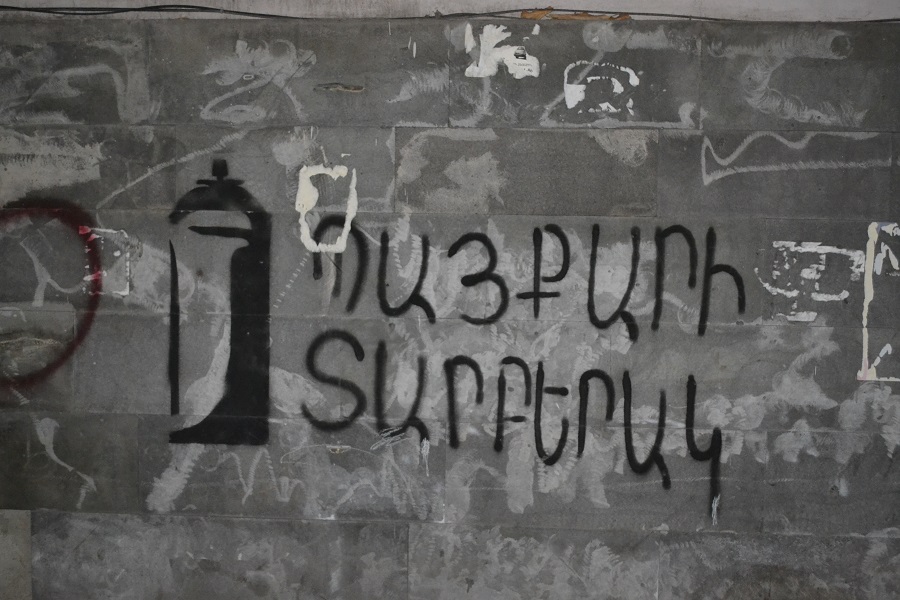

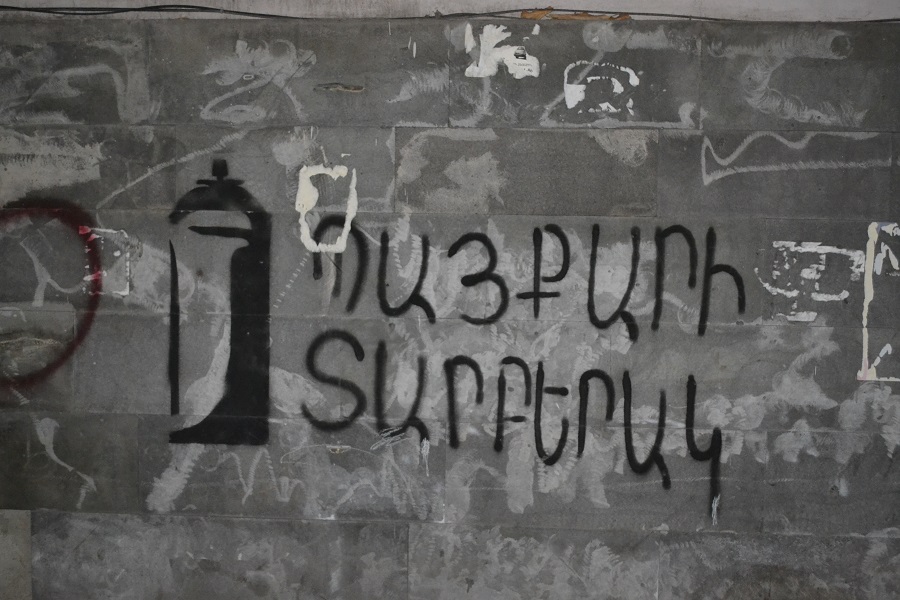

A similar interpretation of reality inspired an unknown street artist in Georgia to make a number of drawings. The first photo was taken on May 18, 2012 in Tbilisi. It was during the then President Mikheil Saakashvili’s second term in office. It has been widely believed that back then the government systematically violated the citizens’ privacy. Secret phone surveillance was so prevalent that nobody felt safe. The obtained materials were used for blackmail and political repression. Distrust and fear were rooted in all the layers of the political and social structure. “Big Brother is Watching You” was written onto walls in central Tbilisi, among them the wall of the National Parliamentary Library of Georgia and the underground passage of Liberty Square.

“Big Brother is Watching You”. Artist: Unknown. Location: Tbilisi, Georgia. Photo Credits: Maia Shalashvili. Date of the Photo: May 18, 2012.

More Here

** Read Part 2 of this Story here.