Current Urban Studies

Vol.03 No.04(2015), Article ID:62067,7 pages

10.4236/cus.2015.34031

Assemblage Thinking and the City: Implications for Urban Studies

Hesam Kamalipour, Nastaran Peimani

2015

The last decade has seen an increasing interest in the application of assemblage thinking, in geography, sociology, and urban studies. Different interpretations of the Deleuzian concept of assemblage give rise to the multiple articulations of the term in urban studies so far. This paper aims to review the recently published research on assemblage theory and explore the implications of assemblage thinking in urban studies. The study thus provides an overview of the most significant contributions in the area, including a succinct bibliography on the subject. The paper concludes that assemblage can be effectively adopted as a way of thinking in urban studies to provide a theoretical lens for understanding the complexity of the city problems by emphasising the relations between sociality and spatiality at different scales.

Keywords:

Assemblage, Urban Theory, Deleuze, Critical, De Landa, Urbanism

Assemblage is one of the key concepts in the Deleuzian philosophy that has been interpreted, adopted, and understood in different ways within the last decade. Assemblage is related to the notions of apparatus, network, multiplicity, emergence, and indeterminacy, and there is not a simple “correct” way to adopt the term (Anderson & McFarlane, 2011) . Reading Deleuze and Guattari (1987) conception of assemblage, De Landa (2006) , as one of the main interpreters of the concept, has critically theorized the multiplicity of assemblage thinking for exploring the complexity of the society. Since then, the concept of assemblage has been adopted in various academic disciplines with different articulations as theoretical and methodological frameworks for exploring the socio-spatial complexities. In urban studies, assemblage thinking has been challenged by various traditions of thinking such as political economy and critical urbanism. Since the 1960s, it has been argued that the city problems are often “complex” (Alexander, 1964; Jacobs, 1961) in a way that the outcomes cannot be simply predicted. Reviewing the recently published research on assemblage theory, the paper addresses its implications for urban studies to conclude that assemblage thinking has the capacity to provide theoretical and methodological frameworks for exploring the complexity of the city problems and the processes through which urbanity emerges in relation to intricate socio-spatial networks at multiple scales.

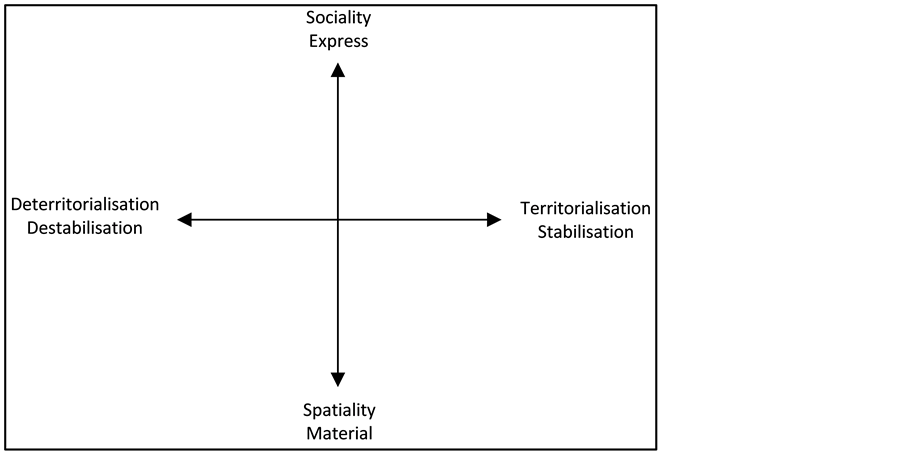

The concept of assemblage has been adapted from the work of Deleuze and Guattari (1987) and applies to an extensive variety of wholes like the social entities generated by the heterogeneous parts (De Landa, 2006) . The idea of assemblage has been addressed as “agencement” that refers to the process of putting together a mix of relations (Dewsbury, 2011) , and in its original French sense refers to “arrangement”, “fixing”, and “fitting” (Phillips, 2006) . Thus, assemblage as a whole refers to the “process” of arranging and organizing and claims for identity, character, and territory(Wise, 2005) . Opposed to the “relations of interiority” in the “organic totalities”, the “relations of exteriority” are characterizing the assemblages as the wholes (De Landa, 2006) . In other words, new identities are generated through connections (Ballantyne, 2007) . In this way, as De Landa (2006) argues assemblage as a whole cannot be simply reduced to the aggregate properties of its parts since it is characterised by connections and capacities rather than the properties of the parts(De Landa, 2006) . Thus, assemblages include heterogeneous human/non-human, organic/inorganic, and technical/natural elements (Anderson & McFarlane, 2011) . Enabling and constraining its parts, the assemblage is an alliance of various heterogeneous elements (De Landa, 2010) . Assemblages are dynamically made and unmade in terms of the two axes of “territorialisation (stabilization)/deterritorialisation (destabilization)” and “language (express)/technology (material)”(Wise, 2005). In a sense, assemblages are at once both express and material (Dovey, 2010) . In other words, assemblages focus on both actual/material and possible/emergent (Farías, 2010) . Assemblages are fundamentally territorial (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987) where territorialisation is both spatial and non-spatial (social) (De Landa, 2006) . In other words, the territory is a stabilized assemblage (Dovey, 2010) . Accentuating the relations and capacities to express and change, orienting towards a kind of experiment-based realism, and rethinking causality and agency, assemblage thinking contributes to the contemporary articulation of social-spatial relations (Anderson, Kearnes, McFarlane, & Swanton, 2012) . In effect, it addresses the inseparability of sociality and spatiality and the ways in which their relations and liaisons are established in the city and urban life (Angelo, 2011) . Hence, assemblage theory is against a priori reduction of sociality/spatiality to any fixed forms/set of forms in terms of processes or relations(Anderson & McFarlane, 2011) . Figure 1 illustrates a conception of assemblage in relation to the two axes of express/material and territorialisation/deterritorialisation.